Currently, around 20% of all deaths globally are linked to poor diet (more than tobacco!). Paradoxically, a worrying percentage of medical students and doctors report receiving less than 2 hours of formal nutrition training. Medicine today is as much about how to prevent disease as it is about diagnosing and treating patients, yet there is this huge disconnect between what we are learning about and what is silently claiming lives. Food systems, corporate marketing, and economic inequality shape public health, but they remain virtually invisible in medical education. This article explores why keeping informed and spreading awareness about nutrition is not just an option, but a moral duty.

If we want to become effective doctors in a world battling an epidemic of non-communicable disease, we need to care about nutrition research.

To make our case, we spoke with Dr Aygul Dagbasi – a registered Dietitian and Postdoctoral Researcher at Imperial College London – who provides expert insights to this article.

1. For Your World: Food Systems that Drive Disease

1. For Your World: Food Systems that Drive Disease

Just like any other industry the food industry runs on profit, but what is less obvious is some of the unethical ways in which that profit is generated.

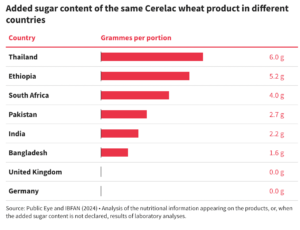

One shocking example is this recent investigation by Public Eye which revealed an unacceptable double standard in the sugar content of Nestle infant formula sold in lower income countries and in Europe.

The only possible aim here is “to get children accustomed to a certain level of sugar at an early age, so that they prefer products high in sugar”. As companies capitalise on confusion around nutritional research, patients get caught in the crossfire. Dr Dagbasi highlighted that “some fat-free and no-added-sugar products – such as certain yogurts – are actually still quite high in sugar” and are easily misunderstood and “dangerously marketed” as very healthy alternatives.

2. For Your Patients: Beyond ‘Willpower’

2. For Your Patients: Beyond ‘Willpower’

Obesity is often framed as a failure of willpower. But as Dr Chris Van Tulleken aptly puts it, the global surge in obesity rates cannot be explained by a worldwide synchronised drop in willpower. UPFs now make up over half of the average diet in the UK and US, offering cheap energy for a hidden price:

-

- These foods hijack our brain’s reward and satiety systems, making them exceptionally addictive. UPFs trigger dopamine release in a similar way to other addictive substances through biologically irresistible combinations of sugar, fat and salt.

-

- Rapid glucose spikes and crashes further drive hunger through hormonal dysregulation (ghrelin and leptin). Sensory enhancing additives and hyper‑palatable textures accelerate eating speed, blunting natural intake controls.

-

- Aggressive marketing, single‑serve packaging, and portion size engineering complete the cycle, making UPF the ultimate profit vessel to override natural physiology and deepen social injustice.

In a landmark 2019 randomised control trial, participants consuming a UPF diet ate around 500 extra calories per day and gained weight within two weeks, compared to those on unprocessed diets. In the last 15 years, the prevalence of obesity in children aged 10-11 has risen by 10% in the most deprived areas of the UK but the change in the least deprived areas is negligible. In adults, the difference in the least and most deprived deciles is 14%. This inequality is systemic.

Dr Dagbasi shared an impactful story of a patient who “lost 6kg and reduced their blood pressure and cholesterol simply by following a balanced diet, without any medication”. Sustained change is possible with the right guidance – health behaviours are significantly influenced by education and health literacy – but to teach our patients about these risks we need to understand them ourselves.

There are unique social justice issues to consider. Even within countries, the food environment is not equitable, and food outlets in disadvantaged neighbourhoods are often dominated by UPFs with limited access to minimally processed foods due to cost and other barriers. UPFs are an important source of calories for many people faced with food insecurity, and this must be acknowledged. Simply creating “UPF phobia” is not productive. Particularly for those who depend on these foods, cutting out UPF altogether is not realistic but reducing their consumption can have the greatest impact. Education and increasing awareness can prevent vulnerable people from developing patterns of overconsumption or even addiction.

3. For Yourself: Why Nutrition Isn’t Fickle Science

3. For Yourself: Why Nutrition Isn’t Fickle Science

Some people dismiss nutrition studies as unreliable because the guidance changes, but this evolution is the foundation of the scientific method. This research is distinctive in that it doesn’t just affect patients with active disease, but it actively affects if and when people develop the disease in the first place. It’s personal; food science gives us an insight into a universal shared human experience – anyone who eats has something to gain.

Dr Dagbasi recalled how the 2016 SACN Vitamin D report changed her practice:

“I now recommend a vitamin D supplement to my patients during winter and autumn because diet alone isn’t enough in the UK.”

Traditional diets, sit-down meals and home cooking are being replaced by convenience culture, dominated by UPFs and fast food to match the pace of modern life. Companies’ vested interests and the influence of corporations unfortunately can have a huge impact on not just what outcomes are reported, but also which studies are even conducted. Even when landmark research is carried out, if it’s not represented in a single guideline, not spoken of in mainstream media, and not modelled by their clinicians, why would anyone care to listen?

While one individual cannot fix a broken system (and doctors are notoriously terrible at this) we must practice what we preach. Every time we change our habits and behaviours, every conscious decision we make to eat differently (under the privilege of choice) ingrains a generation with the knowledge to fight the onset of non-communicable disease. If you’re wondering what the most beneficial change is…

“This depends on individuals current diets but for most people, increasing fibre intake would be the most beneficial change. In UK, people consume around 16-18g when the recommendation is 30g per day. Increasing consumption of fruit, vegetables, legumes and brown carbohydrates would be the best thing.”

The best way to do this is gradually. Dr Dagbasi agrees that “the best strategy is finding a diet that is sustainable for the individual and there is no one size fits all. Most people fail to see improvements in their health because they are making changes they cannot sustain.” Consistency, moderation and balance are the key to making changes that stick.

Summing up

Summing up

Awareness of UPF is spreading fast. The real deficiency lies in how we can translate that into actionable guidance for patients, and a paternalistic approach isn’t going to work. Our population is navigating a noisy world of consumerism and misinformation on a daily basis – we need to be the voices of reason in these spaces to stop people from becoming our patients. Doctors cannot and should not replace dieticians, but they should be able to educate patients on the harms of these addictive foods just as they do with nicotine and alcohol, particularly since UPF is hitting people harder.

Some information sources Dr Dagbasi recommends include:

-

- Research papers in peer-reviewed journals

-

- Researchers, dieticians and nutritionists on social media

Food-related disease is the future of medicine. We’re trained to treat cancer, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, but rarely taught to ask who profits from their cause. Patients already expect us to know about nutrition, and the credibility of our profession depends on it. Over a lifetime, it is estimated we will spend about 4 years just eating and drinking – it’s time for our knowledge to catch up to our appetites. The better we look after ourselves, the better we can care for our future patients.

Sources and further reading

Sources and further reading

-

- Book: Ultra Processed People by Dr Chris Van Tulleken

Thanks for reading. If you have any comments or suggestions, please feel free to share them below and we’ll get back to you as soon as we can!